It’s a special Tuesday edition of the newsletter: a list of 10 not-so-random things for a change! I've mentioned a few times here my ongoing project to categorize and make sense of the various topics I've blogged about over the past 19+ years. A huge chunk (the majority?) were written during the four years I lived in Boston to attend grad school for art (I started the blog just a couple of months into the MFA program here). Nearly 20 years later I'm slowly but surely coming to terms with the reality that I'm not creatively or professionally where I hoped I'd be two decades later. And while I've never had a very rigid vision of what I’d be doing at any point in my life, or sought out a particularly linear path to get there (wrote about this very thing here), I knew what I generally wanted when I applied to the terminal degree for studio art: to be an artist and a teacher. And I'm not really either. I mean, I guess anyone can say they're an artist (I still make stuff but I haven't "officially" shown my work in many years) and I've dabbled in teaching and worked in education and training more broadly, but having an MFA degree did not automatically lead to the dreamy mix of teaching, studio time, and summers off to pursue residencies and such that I imagined 20 years ago.

That said, I am not filled with regret or resentment. The evolution of my feelings about art school is an exercise in contradictions, holding opposing ideas in my brain at the same time. I'm not sure I'd do it again unless it was less expensive and/or I received a better financial aid package. But was it a valuable experience? Absolutely. And as an art school survivor, I feel like this is a fair critique (seems like some of the strongest arguments to skip art school come from creative folks who’ve never themselves been, which I’ve always found somewhat curious). I'm working on a couple of things from the raw material contained within those 113 pages of blog posts, but first, a list!

1. The terminal degree is just the beginning

Establishing a career in art post-MFA is ambiguous and overwhelming. Gaining teaching experience while building an exhibition record is challenging, to say the least. Mentorship was (and still is) valuable and appreciated, but ultimately, navigating your path as a creative person involves a lot of personal trial and error. Expect regular rejection.

On January 19, 2009, halfway through the postgraduate year of my graduate/postgraduate teaching fellowship, 13 months after my MFA thesis exhibition and 8 months after officially graduating, a year or so into the Great Recession, with a 7 month old baby in tow, I wrote this:

I've been feeling a lot lately like I'm not sure how well the MFA degree has prepared me for the next step, or if I'm even sure what the next step should be. I feel like there's this mysterious and overwhelming gap between receiving that terminal degree and really doing anything with it. Or, I should say, doing with it what I'd like to do, which is teach. I feel like I need several more years of teaching experience and a much more impressive exhibition record, but I'm frankly not totally sure how to achieve either, let alone both simultaneously. And while my mentors have been incredibly generous with their time and advice over the past few years, there is this feeling that you have to kind of figure it out on your own.

In other words, the MFA degree is not a guaranteed ticket on the teaching artist train. It’s just one (very expensive) way to embark on this journey (and while we’re exploring this train metaphor, don’t forget to mind the gap!).

2. Location, location, location.

Choose a place to live that aligns with the artistic career you envision for yourself. If you don’t mind winter weather, anywhere in New England is ideal because of its proximity to New York City (if you can afford to live in a borough, even better; as it was we traveled from Boston to NYC via bus 4 times during our 4 years there). Los Angeles is probably where I should have moved at some point during my time living in California. Consider practical aspects like cost of living, day job prospects, and the fiscal health of local art institutions.

When I worked at CCA I overheard more than once the advice that you should get your MFA degree somewhere you plan to stick around for awhile, and while I didn’t do that, I think it’s a good idea. We didn't plan to leave Boston, necessarily. But I didn't think we'd return to the Bay Area, either: housing prices had peaked around the time we left and we didn't foresee them coming down anytime soon. But the recession meant making that leap from grad school to what comes next in Boston equally challenging. We decided to take the lack of prospects in the area as an opportunity to move back to California, but I've always wondered how things might have turned out had I either a) stayed in New England or b) attended grad school in Oakland (at Mills College, specifically). I could have kept one of my two part-time arts admin gigs at the time and built upon the local community I was starting to feel a little bit a part of before moving. Arguably, I could have done this when I moved back. Maybe I could still do it now. That is, however, another list for another day.

3. Make the most of art talks (and networking)

Building on takeaway #2, you don't need to go to art school to attend gallery shows and artist talks. Notable experiences during my MFA years included Kara Walker, Ed Ruscha, Cecily Brown, and Mary Anne Friel. Notable misses that I'll regret until the day I die include Christo & Jeanne-Claude and Maya Lin. Most of the artist talks I attended weren’t necessarily affiliated with my program or school in any way; they were just in the greater Boston area while I was there. Spend some of your art school budget on museum memberships instead.

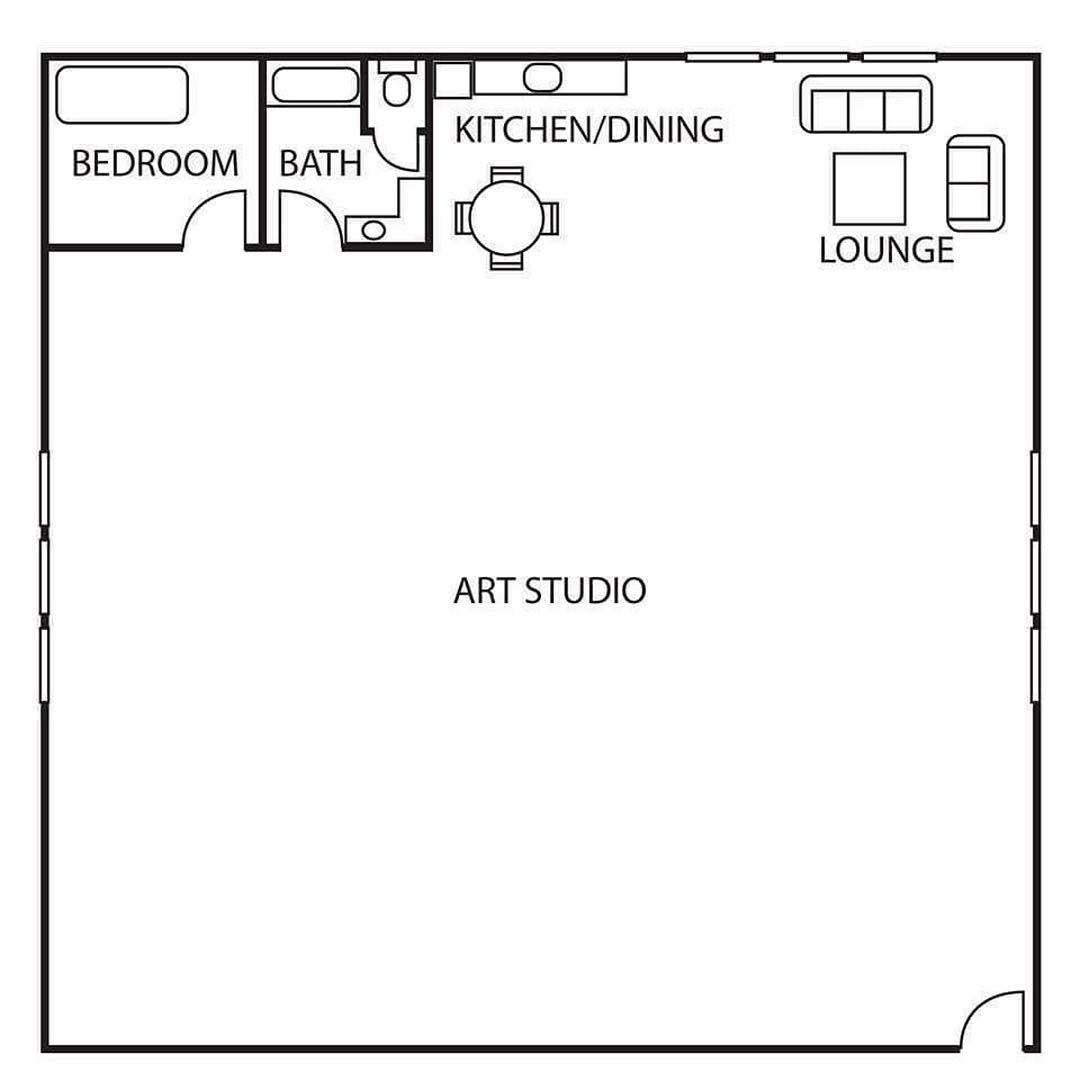

4. Cultivate a creative space

Virginia Woolf was not wrong: every creative person needs a space of their own. Even a small or makeshift space (like a writing nook carved out of half of your closet) dedicated to your art practice can foster creativity. If your preferred medium requires external facilities, find local studios or workshops and explore job opportunities that come with access (such as working at said facilities or as an artist's assistant).

Especially considering how puny the grad studios were at the time (I knew this going into it so it's not like it was a bait & switch or surprise, but still), and compared to the studios I toured on the west coast (including Mills, mentioned above, but also, most drool-worthy, UC Berkeley's MFA studios in nearby Richmond), this is definitely something you don't necessarily need to go to grad school to do/get. Even renting a studio space will pale in comparison financially to what you’d spend on grad school tuition. My creative space has gone through various iterations post-MFA (including a table in the garage, a spare room, a writing nook in my closet, and most recently—where I work now—a 120 square foot backyard studio shed).

5. Play with your art

Once you’ve carved out a creative space of some kind, explore and experiment with different mediums. For me, screenprinting was a logical next step in an anti-painting environment at SMFA at the time because the process emphasized shape, color, and flatness typical of my undergrad painting portfolio, while CMYK techniques allowed me to further explore the relationship between vision and memory. I also enjoyed the physicality of the process (not unlike stretching and priming a canvas). But access to a screenprinting setup post-MFA has been challenging.

Craft techniques like crochet or latch hook shaped my creative style but weren’t always well-received. Balance experimentation with developing practical skills (e.g. design software) for flexibility. The nice thing about not paying for art school is you can spend some of that money on art supplies and exploring new tools and technologies. Likewise, it’s a lot cheaper to pay for an extension course or workshop targeted to exactly what you are trying to learn than a multi-year degree or certificate program.

6. Tales from the Crit

Regular feedback from your peers and professors (second only to access to facilities and faculty/visiting artists) is probably the most valuable thing you'll get from grad school. Social media likes, while appealing, are not constructive. There's no reason you can't set up studio visits and even invite written feedback if verbal critiques feel daunting.

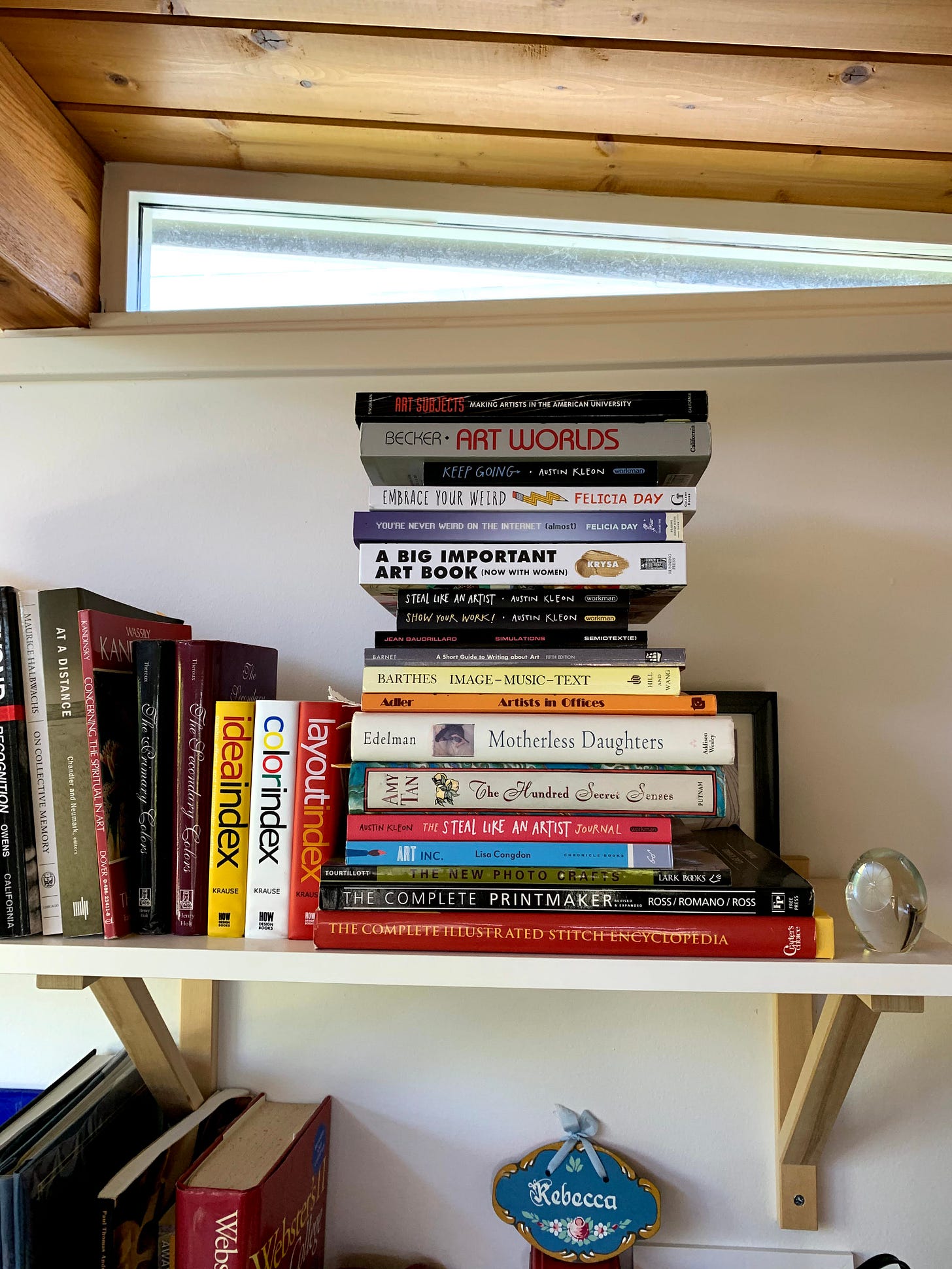

One fun social media thing to search is studio shelfies; see what other artists are reading! Join or start a creative support group in order to foster accountability and inspiration over regular meetups (maybe even over pancakes).

7. Peer Pressure

Peer work can be just as inspiring as professional artist talks. Check out the senior shows and MFA thesis exhibitions at your local art schools and university art programs (usually in late spring each year although some programs may have shows in December, like mine, and/or throughout the winter/spring semester). You don’t have to be a student there to attend the student shows. Student work can offer insights into evolving practices and themes. Likewise, follow the faculty whose work you’re drawn to and see where it takes you and your own creative work.

8. Read the wall text!

Is your phone full of pictures of gallery and museum wall text like mine? Follow the more “academic” influences behind artists’ work you admire. Dive into critical theory current and past that’s relevant to your own work (but don’t get buried in it). Subscribe to blogs or newsletters that discuss art and creativity (like this one!). Write about art—whether through a newsletter, essays, or reviews—as a way to reflect on your own practice. After all, we don’t create art in a vacuum. I found this book very helpful during my undergrad and graduate art history classes.

9. Work less, make more art.

I think there is sometimes a myth that going to grad school will allow you to work on your art full-time. And for some (independently wealthy) students this is true. But between non-studio coursework and the reality that many MFA students have to juggle part-time work alongside their studies to make ends meet, you may struggle to preserve big chunks of studio time as a student. I worked for one academic year in retail at a local mall and then transitioned to campus-based, more creatively adjacent (but lower paying) gigs like teaching assistant, studio monitor, summer high school program mentor, etc. While I genuinely enjoyed and preferred these sorts of experiences over outside work, I also believed the opportunities would help me line up a full-time teaching gig after graduation and that wasn’t necessarily the case (even adjunct positions are often looking for several years’ teaching experience beyond grad school). Whether you’re a student or not, evaluate whether working in the arts or a different field altogether provides the best support for your creative goals (I made a podcast about this!). This isn’t my area of expertise but if, on the other hand, you’re interested in making money directly from your art practice, think about what that looks like. There are loads of great resources out there now about the more practical, business side of being an artist (and this is something, from what I hear, that’s still not really taught in art school).

10. Capitalize on momentum while embracing failure

Whether you go to grad school or not, try standing still long enough to capitalize on existing/growing connections and opportunities. As with any challenging activity, however, eventually you are going to crash and fall flat on your face. Metaphorically, that is. Once you recover initially, you can learn a lot from setbacks. Not every experiment will succeed. Reflecting on these "failures" will be essential for your continued growth as an artist and as a human. You don’t have to embrace your failures publicly, like I do, but I find that self-reflection and writing about things that don’t go as well as I’d like helps me process and move beyond the initial disappointment.

***

In the process of mulling over these blog posts over the last couple of years, I revisited a couple of books on my own studio shelves, including the book that partly inspired my podcast of the same name: Artists in Offices, written by Judith Adler in 1979 about the “academization of art instruction” at Cal Arts. “Teachers in the arts,” she writes, “must find ways to defend themselves against the demoralizing charge that—as it was phrased by one non-teaching member of the Institute’s staff—’it is hardly any service to society to churn out more unemployed people!’” If a common goal out of grad school is to turn around and teach art at the college level, the problem is that there are simply not enough teaching jobs to go around and this is rarely acknowledged.

I’m only just now realizing that one of the most important outcomes of even just applying to grad school was the intentionality of it all. Like declaring your major (I’m majoring in Art! I’m an Artist!!) and the seduction of a portfolio of hard work granting you access to the next logical step in your training as an Artist. I took that acceptance as validation that didn’t necessarily translate to creative or professional success after graduation. The goal beyond that, it seems to me, with or without grad school, is how to maintain that sense of intentionality independent of consistent outside or institutional validation. Maybe this list will help you and me both!